Wine is food (part two)

Sometimes we over-eat

If all be true that I do think,

There are five reasons we should drink:

Good wine - a friend - or being dry -

Or lest we should be by and by -

Or any other reason why.

Henry Aldrich 1647 - 1710 - Five Reasons for Drinking

Working with wine means drinking wine. Drinking wine is both a pleasure and an obligation for those of us who make a living working with it, and when it is good, it is very hard to resist. We are therefore more especially vulnerable to over-consumption.

But there are ways to combat the deleterious effects of the occasional foray into Dionysian excess. Most everyone I know that works in the industry is aware of the benefits of milk thistle for the liver and also physically active, thereby helping to metabolise alcohol quicker. They are also able, by choice, to reserve at least a day or two in the week when no wine (or alcohol of any kind) is consumed. Or, they are capable of limiting their consumption in social contexts and of course spitting during professional tastings.

There is no handbook for dealing with the effects of over-consumption and individual tricks and techniques are varied and inventive. B vitamins are recommended by some, especially niacin, B6 Complex and a B12/Folate combination. Turmeric and milk thistle combined are recommended by some, while the anti-oxidants present in coffee, Brazil nuts and dark bitter green vegetables like cabbage, artichoke, kale, nettle, arugula, mustard, dandelion, watercress, parsley, coriander and rocket stimulate enzyme production and bile flow and also help to detoxify the liver. Fasting and prolonged detox programmes (5 days or more) are practiced once a year by others to give the liver a rest and a ‘reboot’.

But the question is complex because there are several factors that determine the body’s capacity to metabolise alcohol. Body weight, nutrition, lifestyle, emotional balance and genetic makeup clearly show that some people are better at managing their consumption than others.

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism:

Research shows that alcohol misuse and alcohol-related problems are influenced by individual variations in alcohol metabolism, or the way in which alcohol is broken down and eliminated by the body. Alcohol metabolism is controlled by genetic factors, such as variations in the enzymes that break down alcohol, and environmental factors, such as the amount of alcohol an individual consumes and his or her overall nutrition. Differences in alcohol metabolism may put some people at greater risk for alcohol problems, whereas others may be at least somewhat protected from alcohol’s harmful effects.

How alcohol is metabolised

Alcohol is metabolized by several processes or pathways. The most common of these pathways involves two enzymes—alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). These enzymes help break apart the alcohol molecule, making it possible to eliminate it from the body. First, ADH metabolizes alcohol to acetaldehyde, a highly toxic substance and known carcinogen.1 Then, acetaldehyde is further metabolized down to another, less active byproduct called acetate,1 which then is broken down into water and carbon dioxide for easy elimination.2

1 Edenberg, H.J. The genetics of alcohol metabolism: Role of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase variants. Alcohol Research & Health 30(1):5–13, 2007. PMID: 17718394

2 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Alert: Alcohol Metabolism. No. 35, PH 371. Bethesda, MD: The Institute, 1997.

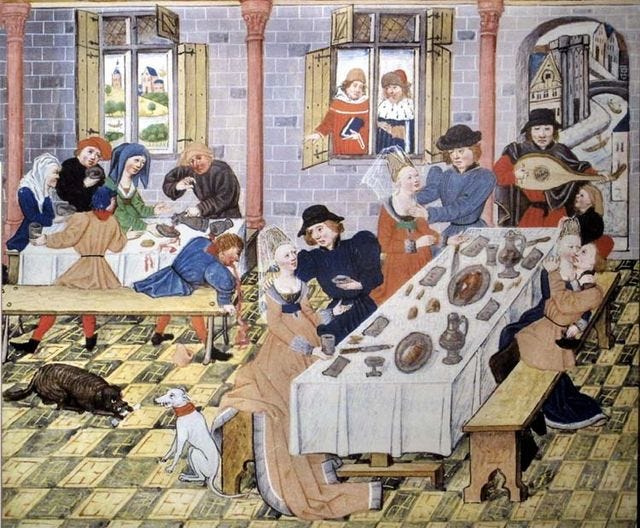

Consumption and over-consumption through history

It is estimated that the clergy in the middle ages were allotted between 2-3 litres of wine per person per day. This might seem excessive and certainly is under normal circumstances, though my own experience of working the harvest in the Côtes de Castillon on an organic farm in the early 1980s resulted in a per-person daily consumption of 3 litres, which means some among us were much bigger consumers than others. Harvest is hard work and so despite the excess, there were no notable side-effects and a very merry time was had by all.

With respect to the religious communities of the Middle Ages, it should be noted that the wines of the Parisian region were lighter and more acidic than the wines of today, ranging between 7-10° alcohol, as opposed to 11-14° (sometimes even 15°) for the majority of wines today. And a third of that wine would have been used for cooking (sauces, vinegar, as additional flavouring) and another third for medicinal purposes. Medieval clergy, monks and nuns, were well versed in herbology and the health-giving qualities of plants and the alcohol in wine provided a perfect milieu for extracting the active ingredients of plants through maceration.

In addition, in a world lit only by fire, daily life was considerably more physical, requiring effort for even the simplest of actions. Metabolising wine would therefore be quicker and the lift it provided in terms of sugars, very welcome when a quick boost of energy was required.

Water sources in urban areas, or downstream from urban centres or areas of industrial activity were often contaminated and so it was safer to drink wine than water, since it was pure. Mixing wine with water was common as well, as this made the water drinkable, microbes and bacteria being killed by the alcohol.

The consumption of alcohol in whatever form was widespread and drunkenness common, especially among the elite, who were renowned for their excessive consumption of wine. Banquets often ended in drinking sessions, with some participants ending up in an alcoholic coma. Though it was associated with the sin of gluttony or over-consumption and was thought to lead to other sins, it was not one of the deadly sins and so those found in a drunken state were not necessarily reproached for it. Drinking in the local tavern was at the heart of urban socializing and such places were the first establishments to open in the morning and the last to close in the evening. Not everyone would get drunk and even fewer displayed the kinds of behaviour that would lead to their ruin. Medieval society therefore adopted a rather permissive attitude towards drunkenness and in the event of a crime, judges often considered it an extenuating circumstance.

As of the 15th century however, a sterner view was taken of drunkenness, which was accused of causing partial paralysis, delirium tremens and other states leading to death. Nonetheless, attitudes towards drunkenness still tended more towards amusement than to criticism eliciting expressions such as ‘drunker than a soup’ or ‘a tipsy tavern pillar’ who had ‘taken advantage of the cellar’s holy water’.

Excess has always been associated with the consumption of wine and there is an entire genre of medieval story-telling that alludes to this connection. In the poem ‘Und swig ich nu’, Oswald von Wolkenstein, a 15th century poet from the South Tyrol whose poems were also set to music, describes the twelve states of drunkenness:

Often a person believes himself to be so wise

and believes to gain highest fame thereby,

when the juice of the grapes has affected him negatively.

The next one believes that he is so rich

that even the emperor might not be an equal to him.

The third appears like an extremely hungry horse,

so no one can push enough of fresh or rotten food

into the ever open mouth.

The fourth one screams cries over his heavy sins,

and his heart is passionately in flames out of deep repentance

for strange reasons that no one can comprehend.

The fifth one desires to do unchaste actions,

to which he is dedicated day and night,

once he has become addicted to the power of wine.

The sixth has a miserable practice:

He condemns the soul through [false] oaths

so that she will be entirely exhausted when facing God.

The seventh is ready to fight, he growls like a dog

held by a chain and who barks all the time;

its round head is ready for a fight.

The eighth becomes so happy out of drunkenness

that he is ready to sell his honour, property, wife, and children;

the evilness of drunkenness shows in him.

The ninth helplessly becomes crazy,

everything what he knows, sees, or hears,

he presents openly to everyone.

The tenth fights against sleep.

The eleventh sings wild songs

and screams totally uninhibited both in the evening and in the morning.

The twelfth becomes so drunk from heavy drinking

that he feels the alcohol already at the top portion of his throat

and voluntarily pays a tribute to the innkeeper.

(translated by Albrecht Classen, The Poems of Oswald von Wolkenstein)

There are countless cautionary tales about the excesses of alcohol in medieval literature so the tendency to drunkenness was obviously of social and moral concern. Consumption of alcohol is still of concern around the world, but anti-alcohol lobbies generally confuse the issue by lumping everything together. Today it is exceedingly rare that health problems from alcohol result from excessive consumption of wine.

WINE, n.Fermented grape-juice known to the Women's Christian Union as "liquor," sometimes as "rum." Wine, madam, is God's next best gift to man.

Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914) - The Devil's Dictionary, 1911

Alcoholism in France was indeed associated with wine fifty or sixty years ago but is today practically exclusively associated with the consumption of ‘hard’ alcohol. It is therefore a statistical error to cite wine as a problem in terms of alcohol abuse. Wine, for the vast majority of wine drinkers, is an accompaniment to food and enjoyed in a discreet and refined manner with friends. Which is not to suggest there isn’t excess, just that excesses in wine consumption are occasional and rarely develop into forms of dependency and abuse.

My appreciation of wine, which is an elevated, complex sensual experience, depends on the sense’s capacity to discern what is in the glass, and keeping fit and attuned to the senses requires a high level of health. In conclusion, moderation (as always) is the key to having a healthy relationship with wine as the body, which is both the instrument of discernment and delectation, is also the recipient and engine that must process excess. Santé!

Thank you for letting me into your world and for reading the Paris Wine Walks Substack. Your support is invaluable as are your comments, suggestions, critiques, dreams, thoughts and remembrances. A little encouragement goes a long way, so please consider a paid subscription, which need cost no more than (a cheap) glass of wine per week. Or, book a wine walk!

My book, ‘The Hidden Vineyards of Paris’ (reviewed in Jancis Robinson’s wine blog, the Wine Economist, National Geographic Traveler UK, UK Telegraph) is available at ‘The Red Wheelbarrow Bookshop’ at 11 rue de Medicis, 75006 Paris. If you haven’t yet discovered this gem of a bookshop, now’s your chance. Open every day!

Wine Walks!

For more information, click on the underlined links:

Sparkling Wine Splash!

Share a sparkling, convivial moment with colleagues, friends or clients to celebrate the moment or to simply gather for fun.

Clos Montmartre - Paris in Your Glass

Paris' most famous wine producing vineyard

Latin Quarter Unbottled!

An insider's journey to the oldest wine neighbourhood in the city

Belleville Unbottled!

A winebar crawl that features some of the best winebars in the city

Wine Your Way Through the Marais

The Marais seen through a wineglass

Saint-Germain-des-Prés

Discover the vinous spirit of medieval Paris

3-Vineyard Cycling Tour

A comprehensive overview of medieval Paris

Paris Bottled!

Short on time? This one’s for you.

I am the 9th, 10th and 11th state.