Every form of addiction is bad, no matter whether the narcotic be alcohol or morphine or idealism.

At this moment I’m sitting on the grass in Paris’ Roman Arena, very close to where I live. The spindly branches of overgrown vines are swaying gently in the summer breeze, quietly absorbing the sun’s rays and storing the carbon they find in the air. Last year’s vintage was disappointing, to say the least, as only 10 litres of wine were made, which I tasted and wrote about in an earlier post. Although it’s far too early to know what this year’s wine will be like, the current weather is promising, and so it’s not overly optimistic to imagine we will finally have a vintage that is a true reflection of this nascent vineyard’s potential.

Fermentation is a largely mysterious phenomenon that science has only been able to grasp in terms of specific chemical analyses. But how to explain the beguiling smells and tastes of wine, and even more so, the effects of ageing? What makes certain wines better than others, and why is the ‘high’ we get from wine so different from that of beer, vodka, gin, or tequila?

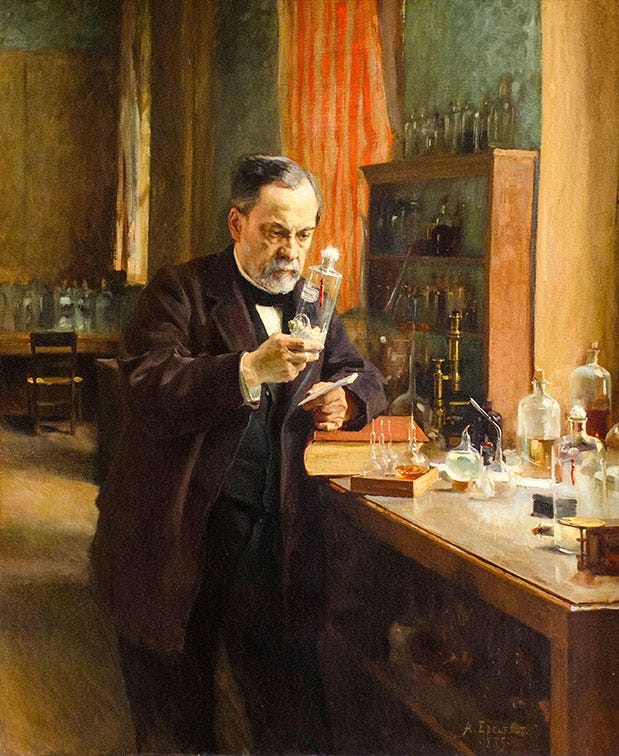

In Science, Vine, and Wine in Modern France, Harry W. Paul tells us that Louis Pasteur studied “an impressive range of fermentations - tartaric, butyric, acetic, and alcoholic. His memoir on alcoholic fermentation (1860) quickly transformed the biological theory of fermentation from Cinderella to princess, who then forced the chemical theory to live among the cinders.” He goes on to tell us that “fermentation produced more than just carbon dioxide and ethyl alcohol: glycerol and succinic acid, along with trace amounts of other ‘indeterminate products’. Without knowing how ferments did all this, Pasteur established a line of research that would eventually make it clear how complex wine really is.”

That wine is complex is an understatement, but there is a great deal of confusion in the manner in which we address this complexity, beginning with the very irksome tendency of health ‘authorities’ and ‘experts’ who somehow imagine that all wine is the same. Fermentation is a very complex process and I’ve given it short shrift here. But the raw material (grapes) that is being fermented causes different reactions and results. Wines with pesticides at the very least give headaches (the whole sulfite thing is a distraction - it’s the pesticides) and most certainly contain carcinogens. Wine that is made with organic and biodynamic grapes give joy, and create a sense of euphoria.

In 2016 I lead a wine tour to Bordeaux with people who have since become friends. We had the rare privilege of tasting vintage wines that were made well before any ‘cides’ (pesticides, insecticides, herbicides, fungicides) existed. It was an uplifting experience that I wrote about with these words:

“You will think that I’m boasting, but I’m not. I’m alive and in a state of joy and wonderment. I’m drunk, but with a drunkeness that is so entirely different from any other I’ve known, I hesitate to even call it drunkeness. Elation, elevation, a profound connectedness and awe of all that creation provides…a delicious surrender to the senses and their astounding capacity to revive, awaken, delight and educate us.

Château Leoville Las Cases 1934

Château Léoville Poyferré 1934

Château Latour 1928

These are the wines we have drunk tonight. We thought we were walking tall in the wheat fields last night with a 1988 Cheval Blanc, but tonight surpassed any wine tasting I’ve ever experienced.

And difficult to share outside of the rarified atmosphere of being in it. Words fail us when the subtleties of what our senses are experiencing exceed our capacities of recognition. We’re in unchartered waters, bobbing about in a sea of pure joy.”

I’ve been recently muddling over the question of ethanol, the alcohol component in wine, in a world that believes that all ethanols are equal, the same, identical. And in a purely technical sense, this is true as the chemical compound (CH3CH2OH) ethanol is the same in all alcohols. And so in terms of how (current) science measures things, all ethanol is the same. But is it?

When I recently asked an oncologist friend if he thought all ethanols are the same, he vigorously responded, “manifestement pas!” Absolutely not! Which is very much what I feel, and though I’ve yet to find anything substantial to back this idea up, it nevertheless seems obvious to me. What spurred this somewhat fruitless query, as again, there is no ‘scientific’ proof of difference, was an article in the New York Times. And it was this sentence, in response to the possibility (which I can affirm) that wine is better for you than other alcohols, that got me going: “Alcohol is alcohol,” said Jürgen Rehm, a senior scientist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto. Drinking any type of alcohol, in any amount, is bad for health.” I don’t want to end up being an apologist for alcohol consumption, but regardless of what the world thinks, it’s clear to me that there are major differences between different kinds of alcohols. And even more specifically, different kinds of wines.

If grapes that are treated with pesticides, insecticides, fungicides, and herbicides, and therefore lacking in vitality, energy, and life, are fermented, the quality of the ethanol must be different from the ethanol that is produced from grapes grown biodynamically in living soils that are bursting with life and vigour. The chemical compound they produce may well be the same, but the resonance, or energy of the one will surely be different from the other. No?

Ultimately the case is moot and perhaps not worthy of the attention it’s not been getting, because, as my wine maker friend Aaron Pott says, “I think the thing you are missing here is that alcohol is only a small percentage of wine. You have phenolic compounds, antioxidants, polyphenols, anthocyanins, tannins, phytoalexines and other compounds that create a beverage around alcohol that is good for you”. I have no doubt that it is these other elements in wine that make it “the most healthful and hygienic of beverages… that nourishes, heals, and enlivens" (Louis Pasteur) but am still of the mind that not ethanols are the same.

If anyone out there is able to shed further light on this subject, I would be keen to hear. In the meanwhile, I encourage everyone to seek the joy in real wine (in moderation of course) and in doing so, not only protect themselves from the dangerous chemicals that can be found in wine, but also support sustainable agricultural practices, and thereby also support efforts to reduce climate change and their own carbon footprint.

Santé!

Thank you for letting me into your world and for reading the Paris Wine Walks Substack. Your support is invaluable as are your comments, suggestions, critiques, dreams, thoughts and remembrances. A little encouragement goes a long way, so please consider a paid subscription, which need cost no more than (a cheap) glass of wine per week. Or, book a wine walk!

My book, ‘The Hidden Vineyards of Paris’ (reviewed in Jancis Robinson’s wine blog, the Wine Economist, National Geographic Traveler UK, UK Telegraph) is available for purchase via our website and at anglophone bookshops and wine shops in Paris. You can also find it at the Musée de Montmartre and the Librairie Gourmande.

Wine Walks & Tastings!

Medieval & Roman Paris

Notre Dame, the Roman Baths, Hôtel Cluny, La Sorbonne, the Pantheon, the Roman Arena… history comes alive, conviviality shines, fun guaranteed, without the wine (or just one glass)

Clos Montmartre - Paris in Your Glass

Paris' most famous wine producing vineyard

Latin Quarter Unbottled!

An insider's journey to the oldest wine neighbourhood in the city

Wine Your Way Through the Marais

The Marais seen through a wineglass

Saint-Germain-des-Prés

Discover the vinous spirit of medieval Paris

Belleville Unbottled!

Join us on this convivial winebar crawl that takes you on an insider's journey to some of the best winebars in the city, tantalizing your tastebuds and awakening all your senses.